Art, trade, and colonialism, then and now

How a contemporary Nigerian-British sculptor updated an old European art motif.

On my last visit to the V&A Museum in London I encountered this striking metal sculpture by the Nigerian-British artist Sokari Douglas Camp. Personifications of Africa (left) and America (right; Indigenous, pre-Columbian, America) support Europe (centre).

At first glance, the figures’ bright, distinctively patterned skirts (more on these later) invoke a sense of celebration. On their heads the figures wear gèlè, fashionable Nigerian head ties. On a closer look, Africa and America look exhausted. Europe stands by virtue of their effort. The garland around the figures looks constraining, reminding one of manacles - and turns out to end in petrol nozzles. The primary material of the work is sheet steel and… recycled oil barrels.

Douglas Camp began to incorporate recycled oil barrels into her work while living in Britain, when her local garage gifted some to her. By using the refuse of the petroleum industry to fashion artworks, she draws attention to how the region of the Niger Delta has been a source of fossil fuels, extracted by multinational corporations, polluting the environment. The working of the figures’ legs leans into the medium, creating a robot-legs effect. There was something dehumanizing about the relationship between Europe and the wider world in the age of European empires.

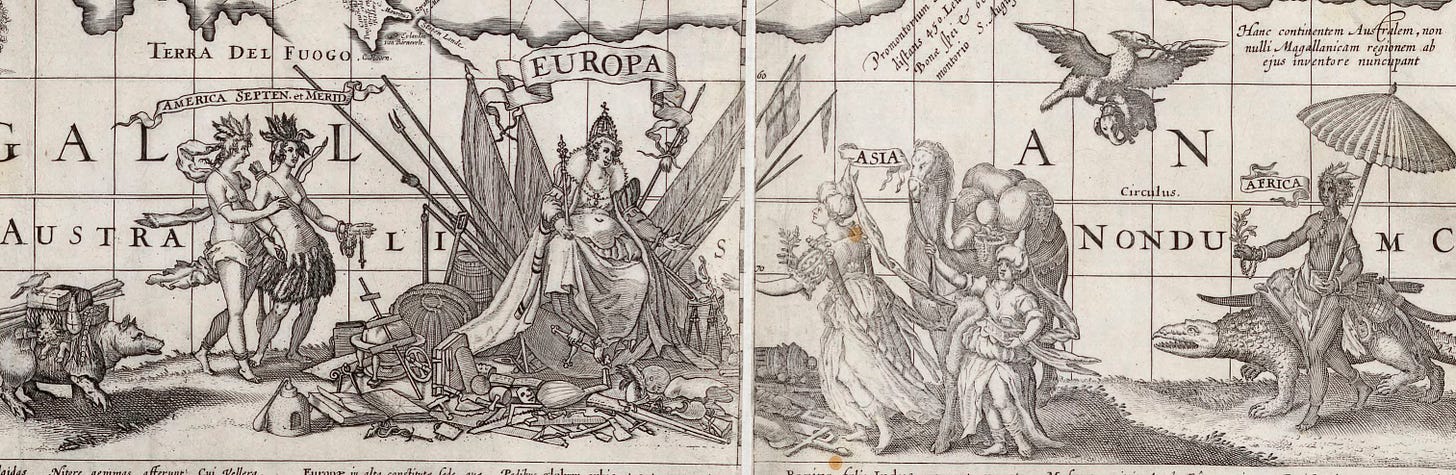

As a historian of cartography (among other things), I was immediately reminded of a motif that appeared on a number of maps printed in Amsterdam at the turn of the seventeenth century. By contrast to Douglas Cooper’s sculpture, these maps depict personifications of the continents (Africa, Asia, North and South America) paying tribute to Europe, or bringing it gifts, rather than supporting a Europe unable to stand on its own legs.

The detail from Pieter van den Keere’s 1619 world map had also appeared on a gigantic, wall map of the world with extensive illustrations around its borders, and published in Amsterdam by Willem Blaeu in 1607. Here, an accompanying poem by one Ricardus Lubbaeus showed viewers how to read the image:

“To whom do the Mexicans and the Peruvians offer brilliant gold necklaces and shining silver jewels? To whom does the armadillo bring skins, sugar cane and spices? To Europe, enthroned on high, the supreme ruler with the world at her feet: most powerful on land and at sea through war and enterprise she owns a wealth of all goods. Oh Queen, it is to you that the fortunate Indian brings gold and spices, while the Arabs bring balsamic resin; the Russian sends furs, his eastern neighbour embellishes your dress with silk. Finally, Africa offers you costly spices and fragrant balsam, and also enriches you with bright white ivory, to which the dark coloured people of Guinea add a great weight of gold.”1

This narrative interprets European military, imperial, and settler-colonial endeavours in a way that allowed European viewers to imagine that their hands were clean.

Well-to-do Amsterdam townsfolk who had made money through transatlantic slavery and other forms of trade involving Indigenous land dispossession or trading agreements set up under the threat of military force could imagine that they enjoyed the global goods like silks, spices, and sugar with the consent of the world’s peoples.

Verbs like “offer”, “bring” and “sends” do heavy lifting here, legitimizing the transfer of wealth. The “Indian” is framed as “fortunate” - for what, I wonder. Lubbaeus’s commentary frames various regions of the world as givers of natural resources - and Europe as the “owner” of these commodities by virtue of force. I’ve written in greater detail about these Blaeu and Van den Keere maps in Chapter Eight of Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human (link at the end of this essay).

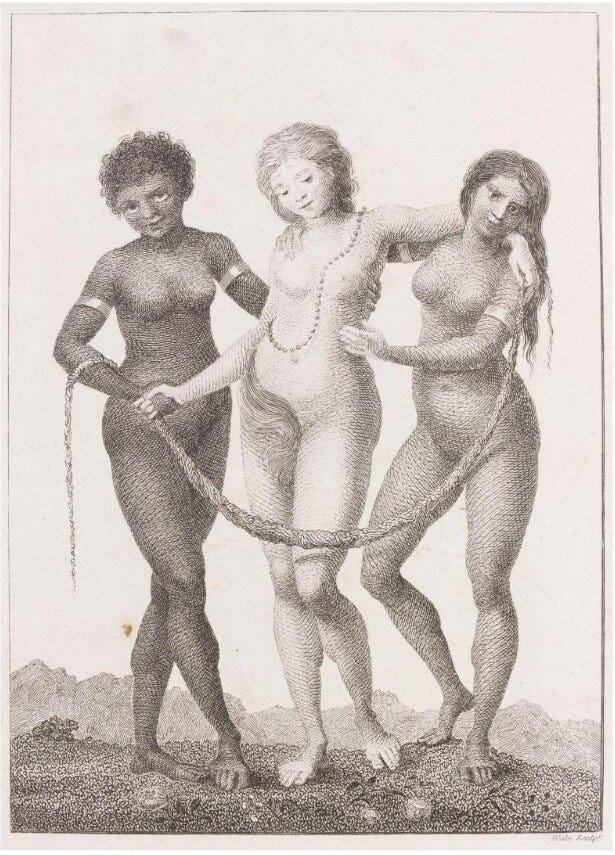

But Sokari Douglas Camp’s inspiration for Europe supported by Africa and America was something else entirely: a print designed by William Blake in 1796, also called Europe Supported by Africa and America. This print was intended as a visual call for the abolition of slavery.

Douglas Camp dressed the personifications in a way that highlights their shared humanity: they all wear headdresses, skirts, and garlands of flowers. By contrast, Blake’s personifications - a remix of the centuries-old “parts of the world” iconography - betray traces of the uneven power dynamic of the time, despite Europe being supported by the Africa and America.

Europe wears a string of pearls and some of her private parts are hidden by her hair. Africa and America have gold bands around their arm that evoke manacles and slavery, and their bodies are more exposed to the viewer’s gaze. This print and others by Blake were published in the Scottish-Dutch soldier John Gabriel Stedman’s account of an extended Dutch military campaign in Suriname against Maroons, or formerly enslaved individuals who had escaped captivity.

For me, Douglas Camp’s sculpture inverts the image of trade and European colonialism propagated by European cartography, as well as speaking back to Blake’s print. The fabric and motifs of the skirts of the sculpture’s figures attest to the entanglement of art, trade, slavery, and colonialism (for the fabrics, see Douglas Camp; links below).

Postscript: Blake’s print was itself a remix of the Three Graces (daughters of the god Zeus), a European motif inspired by classical antiquity. A famous sculptural example by Antonio Canova from the turn of the nineteenth century resides in the same gallery as the Douglas Camp sculpture. Sandro Botticelli’s Three Graces, in his even more famous Primavera panel painting from the late fifteenth century, is in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy.

Takes and recs

Preparing for spring travel, I look around the house and see half-read books that will await my return. Among these is Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140, a quasi-apocalyptic sci-fi novel. Sea levels have risen to completely transform coastal living around the world. The lower half of Manhattan is submerged. There’s an intertidal zone that includes neighbourhoods with skyscrapers, some of which are partially inhabited. There are new wealth (and poverty) paradigms - or perhaps they are the same ones as ever. And… there’s a polar bear cliff-hanger! Run, don’t walk, to this novel, if you can.

What’s happening

In late February and early March, I shall spend just over a week as the Dorothy Ford Wiley Visiting Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Studies at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, USA. In addition to formal and informal events at UNC, I’ll be popping over to nearby Wake Forest University to give a talk. Before and after, I’ll also see friends in DC, and spend almost a week in San Juan, Puerto Rico at the Renaissance Society of America spring conference. Feeling… busy!

References

Sokari Douglas Camp, Europe supported by America, 2015. “Steel, abalone, gold and copper leaf, acrylic paint and petrol nozzles. On loan from the artist, c/o October Gallery.” V&A Museum, London UK. On view for free (along with the V&A’s permanent collection), in Room 21 (Sculpture) until May 14, 2023. Coincides with the Africa Fashion exhibition (2 July 2022 - 16 April 2023; ticketed; a different gallery).

Sokari Douglas Camp writes about this artwork here.

Here’s another essay on Douglas Camp’s Europe Supported by Africa and Asia sculpture and its sources.

For more on Sokari Douglas Camp’s work, see her website.

For European representations of peoples on maps, see my Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human: New Worlds, Maps and Monsters (Cambridge University Press, 2016 [paperback 2017]).

For William Blake’s print, the Stedman volume, and Dutch colonialism, see the V&A catalogue entry here.

V&A events related to the work of Sokari Douglas Camp: https://www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/sokari-douglas-camp

An essay on Canova’s The Three Graces, 1814-15, is at this link.

For an image and catalogue entry for Botticelli’s Primavera, see the Uffizi website.

For the translation of the legend and for additional examples on maps of Europe receiving homage from the other continents, see See Günter Schilder, Monumenta Cartographica Neerlandica, 8 vols (Alphen aan den Rijn, 1986-2013) V, 29–30.

Hi readers! Apologies for a couple of typos and image caption errors. I had two browser windows open as I was proofing this essay - one with the preview, and one I was editing - and then forgot that I had two open, and shut the one with the edits! Going through and putting the alt-text back in and correcting minor errors in caption titles and whatnot...